Why mountain goats are vulnerable in the Black Hills

Published in the Spring Issue of the South Dakota Conservation Digest in 2021

(I added subheadings and a featured quote for this web version)

How do you blindfold a mountain goat? First, you capture the goat by shooting a net gun from a truck or helicopter. Then, you slide protective hoses on the goat’s blade-sharp horns, hobble its legs together, and finally, remove the net so you can blindfold the goat. Your efforts have been successful if you can get a high-frequency telemetry collar around the goat’s neck by the end.

A team of researchers from South Dakota Game, Fish, and Parks put telemetry collars on 47 adult mountain goats in the Black Hills to find their most common cause of death. Today, there are only about 135 mountain goats in the Hills — the highest the population has been in over a decade.

After the first six goats were brought to the Black Hills from Alberta, Canada, their population grew to about 300 goats in the early 1950s. But, since then, estimates have dropped as low as 55 goats in 2011.

“If something catastrophic were to happen, they could disappear,” said Dr. Chad Lehman, a senior wildlife biologist with Game, Fish, and Parks, who designed and led the survival and mortality study from 2006-2018.

Researchers found the most common cause of death

When the telemetry collars emitted a mortality signal, the researchers tried to get on the scene as soon as possible to look for clues like hair, drag marks, or scat. Then, they analyzed the remains for evidence like hemorrhaging or bite marks. In the end, they found that mountain lion attacks were the most frequent cause of death.

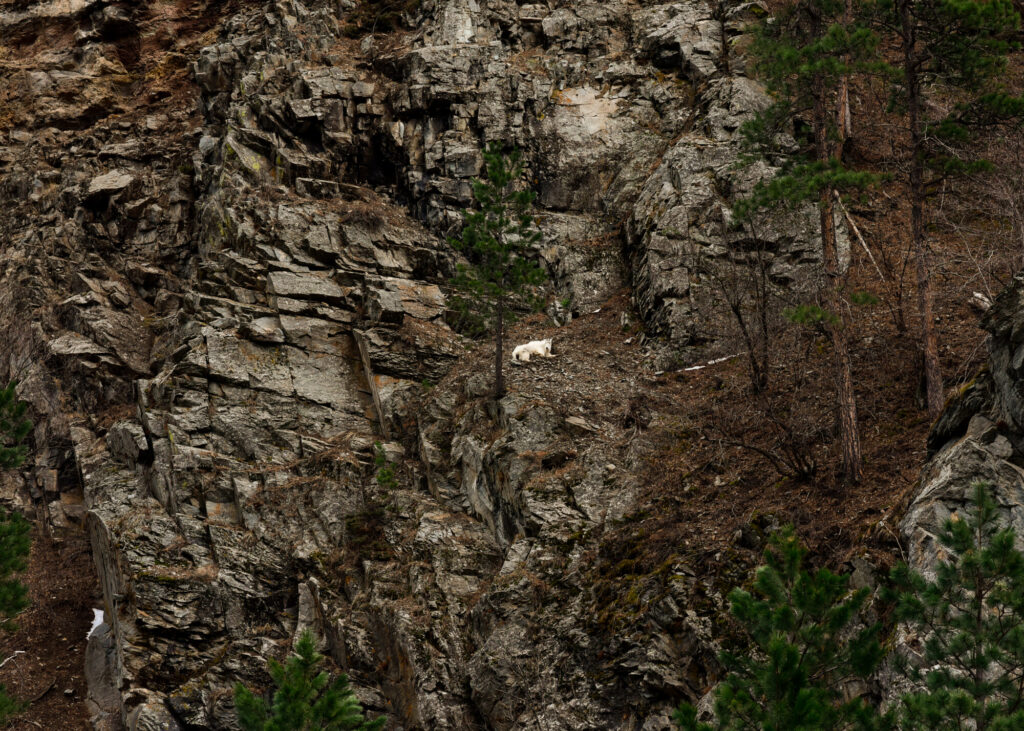

Mountain goats evolved to thrive in open, rocky terrain — they rely on this “escape terrain” to detect and dodge predators. That’s why, if you startle a mountain goat, it might hop onto a sheer rock face and balance on tiny ledges until it’s out of sight.

But, the goats can’t always escape onto rocky ledges in the Black Hills. Sometimes, they need to pass through the forest while transitioning between foraging areas and rocky regions, and mountain lions are capitalizing on that weakness.

"If something catastrophic were to happen, they could disappear."

Dr. Chad Lehman

The tawny predator has learned a special hunting technique to kill the goats in the forest involving waiting for the goats to climb down from the rocks.

“They watch them, and when they disappear into transition zones, they use the trees to stalk within effective killing range,” Lehman said. “Mountain lions can specialize in killing a particular species.”

It seems the goats know they’re in danger because they’ve been observed running when they need to travel through dense pines.

The mountain goat population isn’t large enough to sustain a mountain lion. But, a lion will supplement its primary diet of whitetail deer with the goats, maybe eating the goats 10% of the time. Consistent predation could put the goats in a trap called a population sink where the attacks outpace reproduction.

“If you have 135 goats, and it eats a goat every two weeks, then you don’t have any more mountain goats,” Lehman said.

Mountain pine beetles may help mountain goats survive

One mountain lion may have specialized on the species and killed four of the collared goats in 2007 during Lehman’s study. The population stayed below 76 goats until 2012. Then, something in the ecosystem shifted — and the researchers hypothesized a brown beetle may have helped release the goats from the population sink.

Mountain pine beetles kill pine trees by boring tunnels under the bark. A mountain pine beetle epidemic cleared trees in 86% of the mountain goats’ range by 2012, making it easier for the goats to detect the mountain lions. Lehman’s survival model showed that an increase in mountain pine beetle tree mortality correlated with an increase in the mountain goats’ survival.

The epidemics are cyclical, which spurs cyclical effects on the goats’ survival. Epidemics happen when the forest is dense with pines. The beetle population erupts, and they eat themselves out of food. But, pine trees regenerate quickly, and the mountain goats could become vulnerable again if their habitat fills in with pine trees.

How South Dakota can help the mountain goats

Lehman says clear-cutting the trees in the mountain goat’s range is the most important thing the Forest Service can do for mountain goat survival. Custer State Park has conducted clear cutting of trees in specific areas where the park overlaps with the mountain goat’s range. Not only does this help the mountain goats detect predators, but the open canopy also promotes the growth of forage that the goats like to eat.

Hunters can help the mountain goats by selecting males instead of females. Since reproduction rates are so slow, losing a female mountain goat puts a dent in the population’s growth.

“When you lose an adult nanny, you’re adding to the decline,” Lehman said.

Game, Fish, and Parks issues two hunting permits for mountain goats in a lottery-system each year. But, they’ll stop offering the permits if the goat population dips below 50, or if researchers like Lehman notice the kids aren’t surviving into adulthood.

In the meantime, biologists like Lehman will keep an eye on the mountain goat population through surveys, watching for signs of population decline.