Black bears have returned to South Dakota,

but are they here to stay?

Published in the Fall Issue of the South Dakota Conservation Digest in 2022

Brian was nestled between two pines on a fall morning south of Crystal Mountain last deer season waiting for a couple of grazing deer to come into range. Instead of coming closer, the deer ran away. Brian started scanning the forest.

Less than a minute later, a black bear bounded across the meadow where the deer had been grazing. It’s unusual to see a bear in South Dakota, but Brian wasn’t unnerved.

“I previously lived in Idaho so seeing bears was an every outing kinda deal,” said Brian, who currently lives in the southern Black Hills.

There are more rumors about bears than actual bears in South Dakota. But that doesn’t mean you won’t see one. Biologists have documented black bears all over the Black Hills, in prairie regions, and in parts of eastern South Dakota.

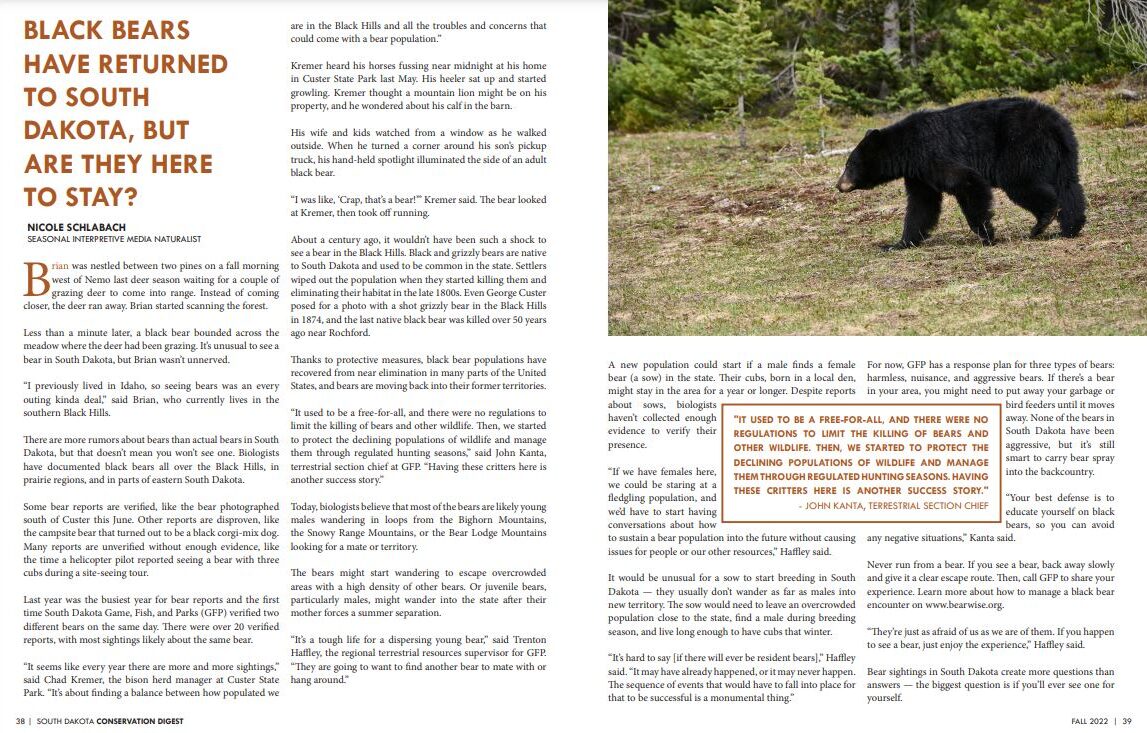

Some bear reports are verified, like the bear photographed south of Custer this June. Other reports are disproven, like the campsite bear that turned out to be a black corgi-mix dog. Many reports are unverified without enough evidence, like the time a helicopter pilot reported seeing a bear with three cubs during a site-seeing tour.

Last year was the busiest year for bear reports and the first time South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks verified two different bears on the same day. There were over 20 verified reports, with most sightings likely about the same bear.

“It seems like every year there are more and more sightings,” said Chad Kremer, the bison herd manager at Custer State Park. “It’s about finding a balance between how populated we are in the Black Hills and all the troubles and concerns that could come with a bear population.”

Kremer heard his horses fussing near midnight at his home in Custer State Park last May. His heeler sat up and started growling. Kremer thought a mountain lion might be on his property, and he wondered about his calf in the barn.

His wife and kids watched from a window as he walked outside. When he turned a corner around his son’s pickup truck, his hand-held spotlight illuminated the side of an adult black bear.

“I was like, ‘Crap, that’s a bear!’” Kremer said. The bear looked at Kremer, then took off running. About a century ago, it wouldn’t have been such a shock to see a bear in the Black Hills.

"It seems like every year there are more and more sightings."

Chad Kremer, bison herd manager at Custer State Park

Black and grizzly bears are native to South Dakota and used to be common in the state. Settlers wiped out the population when they started killing them and eliminating their habitat in the late 1800s. Even George Custer posed for a photo with a shot grizzly bear in the Black Hills in 1874, and the last native black bear was killed over 50 years ago near Rochford.

Thanks to protective measures, black bear populations have recovered from near elimination in many parts of the United States, and bears are moving back into their former territories.

“It used to be a free-for-all and there were no regulations to limit the killing of bears and other wildlife. Then, we started to protect the declining populations of wildlife and manage them through regulated hunting seasons,” said John Kanta, terrestrial section chief at South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks. “Having these critters here is another success story.”

Today, biologists believe that most of the bears are likely young males wandering in loops from the Bighorn Mountains, the Snowy Range Mountains, or the Bear Lodge Mountains looking for a mate or territory.

“It’s hard to say [if there will ever be resident bears],” Haffley said. “It may have already happened, or it may never happen."

Trenton Haffley, regional terrestrial resources supervisor for South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks

The bears might start wandering to escape overcrowded areas with a high density of other bears. Or juvenile bears, particularly males, might wander into the state after their mother forces a summer separation.

“It’s a tough life for a dispersing young bear,” said Trenton Haffley, the regional terrestrial resources supervisor for South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks. “They are going to want to find another bear to mate with or hang around.”

A new population could start if a male finds a female bear (a sow) in the state. Their cubs, born in a local den, might stay in the area for a year or longer. Despite reports about sows, biologists haven’t collected enough evidence to verify their presence.

“If we have females here, we could be staring at a fledgling population, and we’d have to start having conversations about how to sustain a bear population into the future without causing issues for people or our other resources,” Haffley said.

It would be unusual for a sow to start breeding in South Dakota — they usually don’t wander as far as males into new territory. The sow would need to leave an overcrowded population close to the state, find a male during breeding season, and live long enough to have cubs that winter.

“It’s hard to say [if there will ever be resident bears],” Haffley said. “It may have already happened, or it may never happen. The sequence of events that would have to fall into place for that to be successful is a monumental thing.”

For now, Game, Fish and Parks has a response plan for three types of bears: harmless, nuisance, and aggressive bears. If there’s a bear in your area, you might need to put away your garbage or bird feeders until it moves away. None of the bears in South Dakota have been aggressive, but it’s still smart to carry bear spray into the backcountry.

“Your best defense is to educate yourself on black bears so you can avoid any negative situations,” Kanta said.

Never run from a bear. If you see a bear, back away slowly and give it a clear escape route. Then, call Game, Fish and Parks to share your experience. Learn more about how to manage a black bear encounter on www.bearwise.org.

“They’re just as afraid of us as we are of them. If you happen to see a bear, just enjoy the experience,” Haffley said.

Bear sightings in South Dakota create more questions than answers — the biggest question is if you’ll ever see one for yourself.